ST. PAUL, Minn. — As farmers consider adopting soil health practices, it’s important to understand the implications for their operations. By exploring the impacts these management changes have on different aspects of their system, farmers can make the most informed decisions for their businesses and families. Cover crops and reduced tillage are some of the most widely adopted soil health practices. One management technique that often gets overlooked is crop and livestock integration.

Crop and livestock integration is a management approach in which livestock are part of an annual cropping system. The cropland provides feed for the livestock, and the livestock provide nutrients to the cropland. Common crop and livestock integration practices include:

- Grazing cover crops

- Grazing crop residues

- Grazing annual or perennial forages

- Bale grazing on cropland

The soil health benefits of integrating livestock are well documented, but many folks wonder about the financial implications, especially if they don’t already have both enterprises as part of their farm. To study the economics of crop and livestock integration, a group of Extension professionals from four states (IA, MN, MO, and WI) collaborated on a research project.

Research background

Extension professionals collected 2024 financial data from eleven integrated farms across four states (IA, MN, MO, and WI). These farms had an average size of 964 acres, with 32% in crops, 16% in hay, and 52% in pasture. The data was entered into FINPACK financial software from University of Minnesota’s Center for Farm Financial Management.

Integrated farms were compared to a similar dataset of crop-only farms. Crop-only farm data came from FINBIN, a farm financial database that summarizes farm data from FINPACK to provide financial benchmark information. The subset of crop-only farms for this study included 601 farms across three states (MN, MO, and WI), with each managing between 501-1000 acres of cropland.

Research results

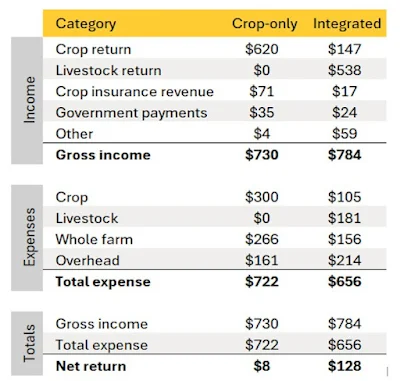

In this study, integrated farms had more income and fewer expenses than crop-only farms. This means that overall, integrated farms had a higher net return on a per-acre basis than their crop-only counterparts. The table below shows the breakdown of average income, expenses, and totals on a per acre basis.

While crop-only farms had higher income from annual crops, they also had greater crop expenses. Integrated farms used about 68% of their land for forage crops which tend to have lower crop inputs, while crop farms used 100% of their land for annual crops which have higher fertilizer, ag chemical, and seed costs. The integrated farms also had income and expenses from livestock that the crop-only farms didn’t have. Crop-only farms spent a little more on whole farm expenses such as fuel, repairs, custom hire, land rent, trucking, and marketing. Integrated farms spent a little more on overhead expenses such as hired labor, utilities, leases, taxes, and farm insurance.

Conclusions

This study showed that on average, farms that use crop and livestock integration practices are more profitable than crop-only farms. There are a few reasons why this might be.

- Diversification of enterprises allows for resilience to changes in markets. The livestock enterprise can help buffer income when crop prices are low. Similarly, the crop enterprise can help buffer income when livestock prices are low.

- Resource efficiency can help reduce costs. Grazing livestock on crop residue or other forages on cropland can reduce the amount a farmer needs to spend on feed each year. Livestock also provide nutrients to the cropland via manure, potentially reducing the amount of fertilizer that needs to be applied.

- Forage crops can be less expensive to produce. Forages require fewer crop inputs and can be produced on lower value land, reducing both production costs and land costs.

Crop and livestock integration is a management strategy that focuses on long-term farm viability. The balance between short-term profit and long-term viability can be difficult to grapple with. Specializing in one enterprise creates efficiencies but also involves long-term financial risk. Farms that have both crops and livestock may be able to better withstand fluctuations in market prices, leading to increased long-term farm viability.

Click here to view more information on this research.

For the latest nutrient management information, subscribe to the Nutrient Management Podcast. And don’t forget to subscribe to the Minnesota Crop News daily or weekly email newsletter, subscribe to our YouTube channel, like UMN Extension Nutrient Management on Facebook, follow us on X (formerly twitter), and visit our website.